Blog |

Busting the ‘Dirty’ Myth of Corporate Environmental Lobbying

It’s environmental gospel that U.S. industry engages in political activity — like political donations and lobbying — to oppose regulation.

But in the United States, the largest spenders on lobbying turn out to be both those “dirty” firms that emit a lot of greenhouse gases and those “clean” firms that emit comparatively little.

That finding comes out of new research authored by Magali Delmas, a professor of management in UCLA’s Institute of Environment and Sustainability as well as UCLA’s Anderson School of Management. Their findings were recently published in the Academy of Management Discoveries.

Delmas and her co-authors looked at 1,141 firms doing business in 18 sectors from 2006 to 2009 — sectors ranging from automobiles to chemicals to food and beverages to oil and gas to utilities. These firms spent a combined $1.1 billion in climate lobbying during that period.

The researchers found that clean firms also invest in lobbying in support of governmental regulations as a business strategy to gain market advantages over their competitors.

In fact, one of the greenest utilities in the nation, Pacific Gas and Electric, spent an estimated $27 million lobbying on climate change at the federal level in 2008.

“In addition to the usual suspects, greener firms are also attempting — and perhaps competing — to influence legislative outcomes,” says Delmas. “This challenges the conventional view that corporate lobbying is always adversarial to environmental regulation.”

A Breakthrough: Corporate Lobbying and Environmental Performance

Despite the fact that lobby expenditures are consistently five times larger than Political Action Committee contributions, Delmas’ new article is the first to examine lobbying expenses as a measure of the relationship between environmental performance and political activity.

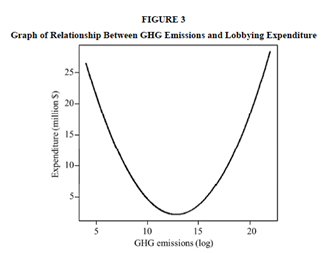

Using novel, issue-specific data on lobbying expenditures (which has only recently become public electronically), Delmas and co-authors established a U-shaped relationship that shows firms devote increasing resources to influence public policy — both against and in favor of regulation — as they approach either end of the environmental performance spectrum. (See figure.)

Delmas says that, while firms with poor performance on environmental issues will likely view regulation as a threat to profitability and wish to preserve the status quo, firms with exemplary performance may perceive regulation as an opportunity to engender market conditions that favor good performance.

The research also affirms, she says, what the economic theory of regulation has long argued: that firms can often obtain private benefits by promoting environmental regulations, which can engender barriers to entry and create other sources of competitive advantage.