3 alumni Nobel laureates recount how UCLA set them on a path to the prize

From the lecture halls of Westwood to the world’s most prestigious scientific stage, UCLA’s Nobel-winning alumni trace their triumphs to a common source: a public university that opened doors

As this Nobel Prize season draws to a close, a ninth Bruin alumnus has joined the ranks of the world’s most celebrated thinkers — those whose discoveries have profoundly advanced knowledge and improved lives.

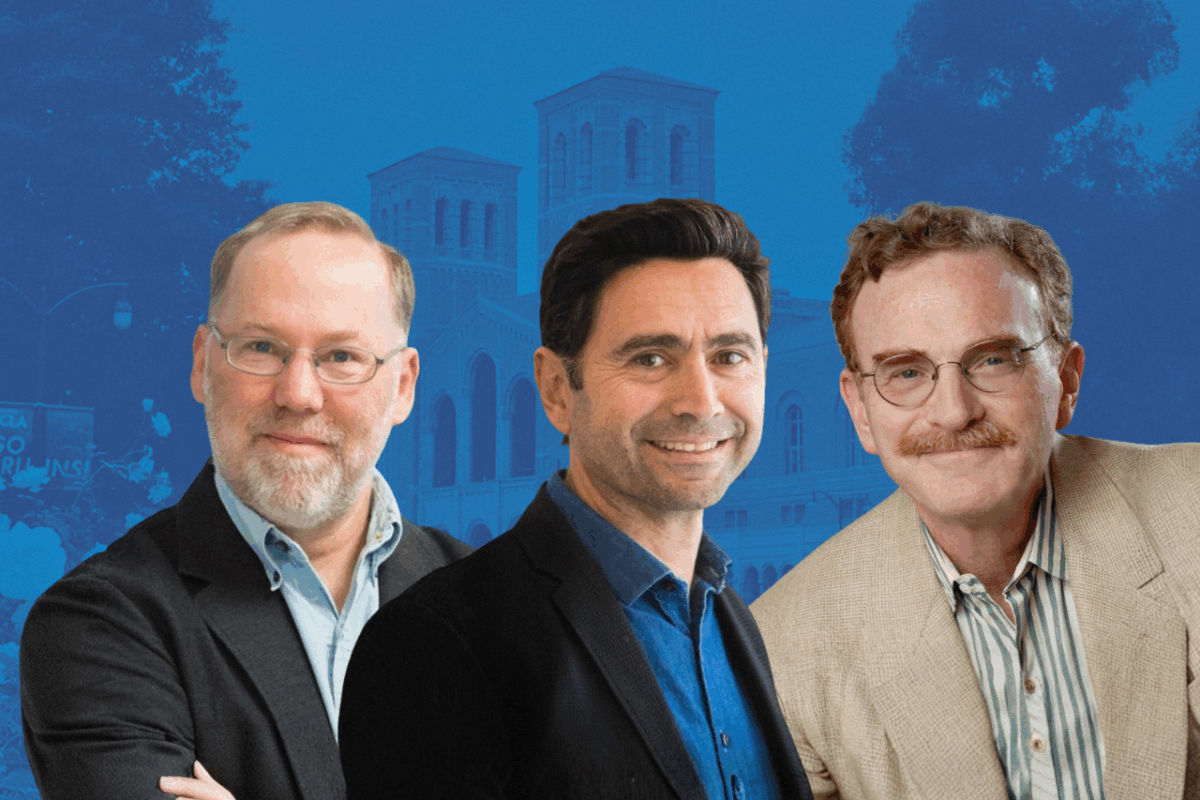

And in leaving an indelible mark on science, UCLA’s three most recent alumni Nobel laureates — all honored in the category of physiology or medicine — say their experience as UCLA students looms particularly large.

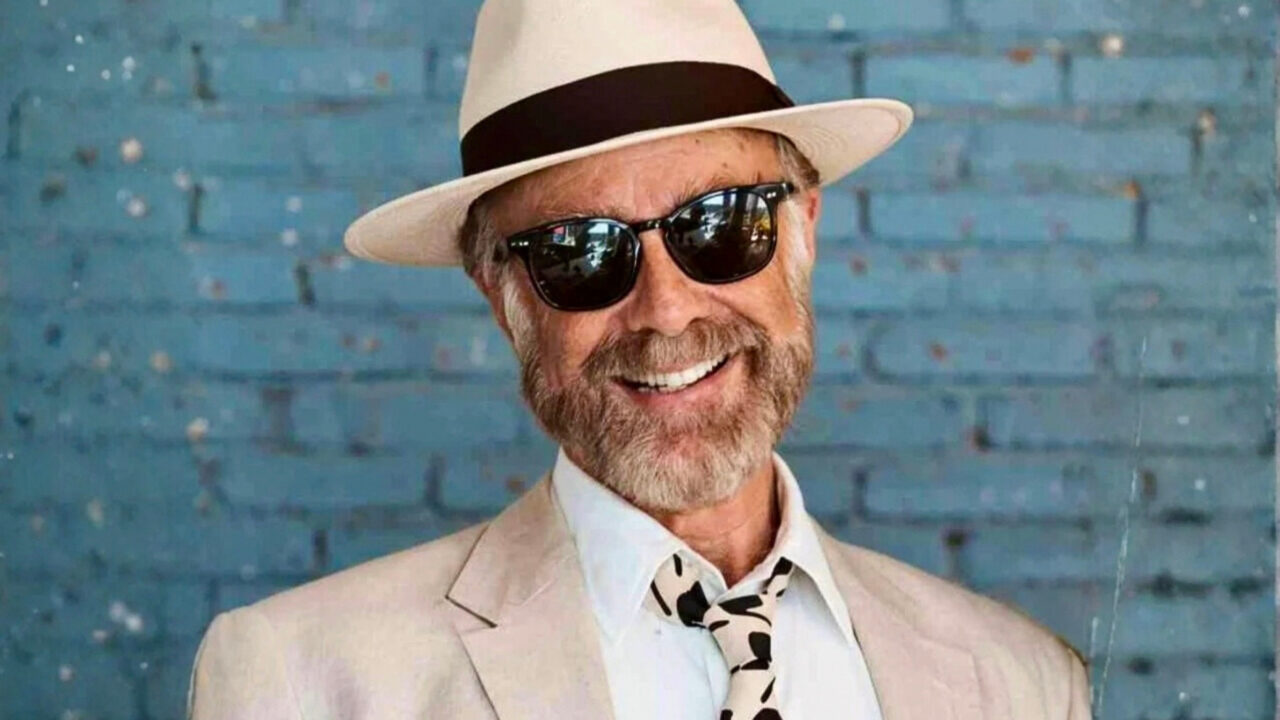

For Frederick J. Ramsdell, who won the prize Oct. 6 and whose path to UCLA started at a California community college, UCLA’s spirit of scientific collaboration and knowledge-sharing has characterized his entire career in biotechnology.

For Ardem Patapoutian, an immigrant student and the winner of the 2021 prize, lab work and the mentorship of UCLA’s world-class faculty changed the trajectory of his life.

And for Randy Schekman, who was honored in 2013, working in UCLA research laboratories helped define his focus and launch his career as a molecular biologist.

Ramsdell, Schekman and Patapoutian recently spoke with Newsroom about their backgrounds, the national importance of accessible and well-funded higher education, and how the opportunities and resources they first found in Westwood played a vital role in their scientific journeys.

Their stories are powerful reminders that UCLA and other major research universities — when sustained by government investment — are engines of discovery, creativity and social mobility and that long-term support for education and science yields transformative benefits for society.

Accessible education, mentorship and federal science funding

“I’m a California kid through and through, from an education perspective,” said Ramsdell, whose journey took him through every level of public higher education.

Unable to afford a four-year college directly out of high school, Ramsdell — like 1 out of every 4 current UCLA undergraduates — initially attended a community college. His studies at Foothill College in the Bay Area provided a springboard to a bachelor’s degree in biochemistry and cell biology at UC San Diego and ultimately to a Ph.D. in microbiology and immunology at UCLA.

As a doctoral student at UCLA, Fred Ramsdell trained cancer surgeons in laboratory work. That knowledge-sharing approach to scientific research would become a mainstay of his work in the biotech industry, and a key ingredient of Nobel Prize-winning research.

“My love of immunology was born in college,” Ramsdell said. And at UCLA, that love was nurtured by medical school professor Sidney Golub, an expert on cancer-killing immune cells, whom Ramsdell called “a fantastic mentor.”

Golub, now a professor emeritus at UC Irvine, encouraged Ramsdell to work with colleagues outside his field through nationally funded training programs and even arranged for the then-second-year doctoral student to train cancer surgeons at UCLA in laboratory work.

“He said, ‘They know stuff that you don’t know, and you know stuff that they don’t know,’ and he was right,” Ramsdell recalled. It’s a lesson he applied in his career. “I went into biotechnology because it’s an incredibly team-oriented environment. I got to work with people who were as good as anyone in the world at what they did, and I didn’t have to be, because they were great at it — and I knew stuff they didn’t know, just like Sid said.”

Ramsdell, a founder of and scientific advisor for Sonoma Biotherapeutics in San Francisco, won the Nobel Oct. 6 for his groundbreaking findings on how the human immune system patrols itself and prevents immune cells from attacking the body’s tissues. His work could lead to new therapeutic options for people with autoimmune diseases like arthritis, multiple sclerosis, Crohn’s disease and other disorders.

A pivotal part of that award-winning research, which relied on support from the National Institutes of Health, involved a highly unusual strain of mice whose immune systems attacked their own organs — a strain that had been continually bred and maintained by federal government scientists since the 1940s in the hope that at some point it would prove useful. Ramsdell noted with concern that withdrawing support from these types of projects could threaten scientific advances.

“They knew it was interesting but didn’t have the tools to figure out why. Years later, we did,” Ramsdell said. “That’s an example of the government investing in basic science in the 1940s, and it eventually led to not just this Nobel Prize but to clinical trials right now with patients with disease to see if we can make them better. The idea of those long-term investments being eliminated and downgraded is a very shortsighted way to think about science.”

UCLA ‘changed the trajectory of my life’

After emigrating from war-torn Beirut in 1986 at the age of 18 with the dream of pursuing a college education, Ardem Patapoutian, who had left his parents behind in Lebanon, spent his first year in Los Angeles working odd jobs to establish residency and qualify for in-state tuition. “I didn’t even know what a Pell Grant was,” the Nobel laureate said of the federal financial aid that would made his UCLA education possible.

It was in Westwood that he would find his calling. “UCLA was where I first discovered the excitement of scientific discovery,” he said. And while his first ambition was to attend medical school, two formative undergraduate experiences changed his outlook and steered him toward an award-winning career as a basic research scientist.

“UCLA was where I first discovered the excitement of scientific discovery,” said Ardem Patapoutian, whose journey from Beirut, Lebanon, to UCLA would set him on the path to the 2021 Nobel Prize.

One was an introductory biology class focused on DNA taught by molecular biologist Bob Goldberg, the other an opportunity to work as an undergraduate researcher in the lab of Judith Lengyel, herself a UCLA alumna, whose federally funded research centered on the development of organs in fruit fly embryos.

“Working in Judy Lengyel’s lab and taking Bob Goldberg’s molecular biology course opened my eyes to research as a calling rather than a requirement for medical school — it truly changed the trajectory of my life,” Patapoutian said.

Today, approximately 45% of UCLA undergrads participate in some form faculty-driven research, from the sciences to the arts, and many work in the labs of professors conducting basic research across the STEM spectrum.

► Meet some of the thousands of UCLA students whose research was featured during Undergraduate Research Week in 2004 and 2005.

Coinciding with his graduation in 1990, Patapoutian published his first paper in a scientific journal as a co-author with Lengyel. “I was thrilled,” he recalled.

Armed with those experiences, he would go on to earn his doctorate in biology from Caltech and join the Scripps Research Institute in San Diego, where his work on how temperature and touch are converted into electrical impulses in the nervous system would bring him the Nobel Prize in 2021. Those findings, fueled by multiple investments from the NIH, are being used to develop treatments for a wide range of diseases and conditions, including chronic pain.

Patapoutian stressed the crucial importance that student research opportunities play in higher education, drawing the best and brightest from all walks of life from California, the nation and the world to UCLA and allowing burgeoning young scientists to explore new horizons.

“This country,” he said upon receiving the Nobel Prize, “gave me a chance with a great education and support for basic research.”

‘A direct line’ from UCLA to a Nobel-winning career

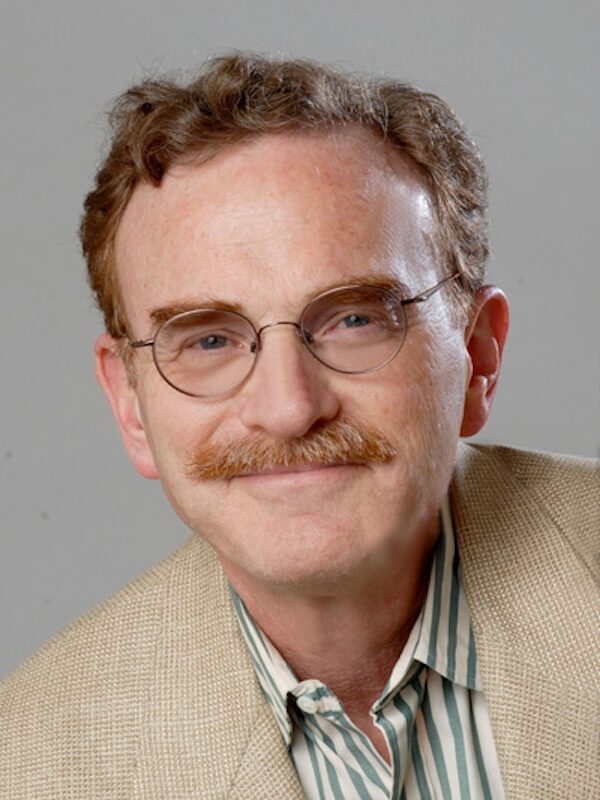

Molecular biologist and UC Berkeley professor Randy Schekman, who won the Nobel Prize in 2013 for his work on how proteins are packaged and transported in cells, earned his bachelor’s degree from UCLA in 1971. He characterized his academic and research experiences at the university as “absolutely essential” to his work. “There’s a direct line from what I did at UCLA to my eventual career,” he said. “UCLA changed my life.”

One of five kids from a California family, Schekman, like Patapoutian, had his heart set on becoming a physician — until he did so well in his first-year chemistry class that he earned a spot in an honors chemistry course with UCLA Nobel chemistry laureate Willard Libby and the opportunity to work in the lab of another professor, who introduced him to James Watson’s seminal 1965 book “The Molecular Biology of the Gene

“The ‘real world’ comes to UCLA,” said Randy Schekman, who stressed the role of the university in helping students from middle- and working-class families build a better life. Schekman donated his 2013 Nobel Prize money to support research at the University of California.

The book, Schekman said, was a revelation, and it spurred him to pursue further research in the lab of Dan Ray, where he worked on the replication of DNA viruses and even ran his own experiment. “In that lab,” he said, “I realized I was going to be a scientist, not a physician. I told my parents I wasn’t going to medical school anymore. They were a little disappointed, but they got over it.”

As an undergrad, Schekman was also able to publish several papers, co-authored with Ray, in major scientific journals, which helped him land a spot as a doctoral candidate in Stanford University’s biochemistry department — “the best biochemistry department in the world at the time,” he said. “UCLA gave me the launching pad I needed to make a career.”

Schekman’s federally supported Nobel-winning research would ultimately provide insights into neurological diseases, diabetes and immunological disorders.

In June 2014, less than a year after his Nobel honor, Schekman, who donated his Nobel winnings to the University of California, returned to Westwood to talk to graduating students as keynote speaker at the UCLA College commencement.

“The University of California has provided generations of middle- and working-class families with an opportunity to build a better life,” Schekman said, highlighting the importance of an affordable, accessible college education. “The ‘real world’ comes to UCLA.”

► Video: A UCLA Newsroom conversation with Nobel laureate Randy Schekman (2011)

The current uncertain environment around scientific research and funding in the U.S. — which threatens not only the type of Nobel Prize–winning research UCLA’s alumni laureates conducted but the research opportunities they were able to take advantage of as undergraduate and graduate students — was top of mind this Nobel season.

“Labs that close down won’t be able to support their undergraduate researchers,” Schekman emphasized. “And that was the thing that launched my career — having the opportunity to work in a research lab at UCLA.”

Fred Ramsdell was one of five University of California faculty and alumni Nobel Prize winners in 2025.

In addition to Ramsdell, Patapoutian and Schekman, six UCLA graduates have won the Nobel Prize: Richard Heck (chemistry, 2010), Elinor Ostrom (economic sciences, 2009), William Sharpe (economic sciences, 1990), Bruce Merrifield (chemistry, 1984), Glenn Seaborg (chemistry, 1951) and Ralph Bunche (peace, 1950).

Eight UCLA faculty members have been named Nobel laureates: Andrea Ghez (physics, 2020), J. Fraser Stoddart (chemistry, 2016), Lloyd Shapley (economics, 2012), Louis Ignarro (physiology or medicine, 1998), Paul Boyer (chemistry, 1997), Donald Cram (chemistry, 1987), Julian Schwinger (physics, 1965) and Willard Libby (chemistry, 1960).

UCLA’s most recent alumni Nobel laureates, all of whom won the prize in physiology or medicine (left to right): Fred Ramsdell (2025 laureate), Ardem Patapoutian (2021) and Randy Schekman (2013). Photos courtesy of Fred Ramsdell, Scripps Research Institute and Peg Skorpinski / Collage: UCLA