Ary Amaya is 27 acres into an Indigenous-led reforestation of L.A. She’s far from done

The UCLA graduate student is helping ensure that Native ecology drives the region’s land management for centuries to come.

Ary Amaya barely squints as she stands awash in the midmorning glare, which reflects off the dew clinging to the tall grasses that carpet the ground. Anchoring herself on a dirt path that crests a large hill, she scans the descending slope covered in walnut, toyon, oak and elderberry trees.

The double Bruin, now in the final year of her master’s program in ecology and evolutional biology, knows the land well. She explains how the trees, some of which she and her research team have planted, make up a “food forest” — a collection of plants and trees she says are culturally significant to the Indigenous peoples who are the stewards and keepers of the land.

The hill is part of a 12-acre open space in northeast Los Angeles, acquired in 2022 for the Gabrielino-Shoshone Nation of Southern California. It was named the Chief Ya’anna Regenerative Learning Village in honor of Chief Ya’anna Vera Rocha, the tribe’s late chief.

Amaya says the acquisition marked the largest land rematriation to date by Indigenous peoples in Los Angeles.

At the center of the rematriation and reforestation work is the Anawakalmekak International University Preparatory of North America, a community-based charter school in the El Sereno neighborhood of East Los Angeles. The K–12 campus, currently the only Indigenous school in the city, serves Indigenous peoples from across the United States, Canada, and Central and South America.

Amaya, an educator at the school since February 2021, has helped develop scientific curricula centered on Indigenous practices, language and knowledge. Her understanding of these “Indigenous knowledge systems” was engrained in her long before her graduate program and employment at the school.

She is a descendent of traditional farmers and medicinal knowledge keepers from the pueblos of Amatlan de Jora, Ixtlan del Rio and Huajicori, in the southwest regions of Nayarit, Mexico. Amaya was born in Santiago Ixcuintla, Nayarit, before moving to East Los Angeles with her mother and sister.

Her role at Anawakalmekak, where she started as community organizer before evolving into a hybrid teacher, has opened up a channel between the school’s Indigenous-led reforestation and UCLA.

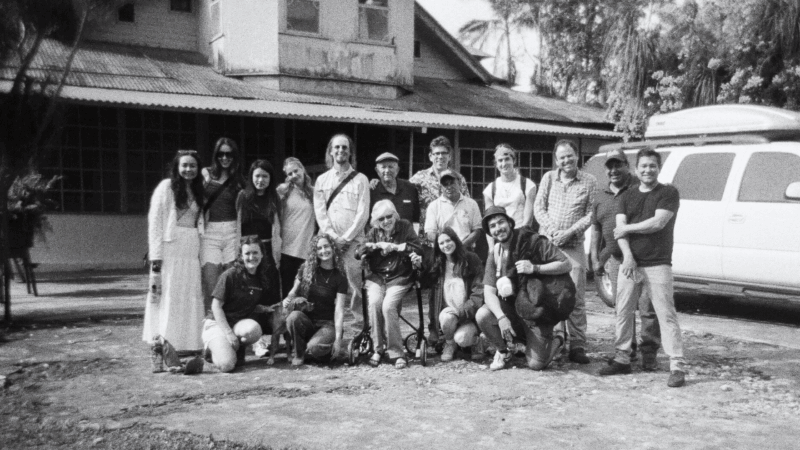

With the support of her graduate advisor, UCLA ecologist and environmental biologist Elsa Ordway, Amaya has brought in Indigenous migrant youth to assist in her graduate work — specifically the reforestation of the village and 15 acres at Ernest E. Debs Regional Park, an open space in Los Angeles’ Montecito Hills neighborhood. The two sites bring the scope of Amaya’s current work to 27 acres and counting.

Five of these youths, all high school students at Anawakalmekak, make up Amaya’s “Ketsal Youth Research Scientists.” Every week, they engage in ground observations at the village or the park, monitoring newly planted trees and measuring the canopy of mature trees. The changes in canopy coverage, which can be observed using airborne and satellite imagery, can signify environmental impacts that cause changes in the ecology over time, Amaya says.

These ground observations differ from what Amaya says are more Western ecological study practices, such as the use of data from satellite and aerial footage to tell the land’s story. The study of this footage is referred to as remote sensing and is something that Amaya has her youth researchers utilize to compare with what they observe on the ground.

“These students are helping us think about how we as Indigenous people not only reforest and reenvision what ecological restoration looks like in the city, but also how that’s rooted in Indigenous sovereignty and self-determination — and how can we begin to quantify that in measures of what academia deems appropriate,” Amaya says.

“We have our own ways of understanding the health of the ecosystem and its progression, so I’m really trying to integrate both of those worlds.”

The work has strong ties to what Amaya has been involved with in Ordway’s Forest Ecosystems & Global Change Lab at UCLA, which conducts international research and fieldwork to study how ecosystems are responding to climate change and its key drivers, like human deforestation, and associated carbon emissions. Amaya says that understanding these changes on a large scale is key to sustaining the forests and agriculture of Indigenous peoples.

“I was looking for an advisor who would take me on, not only as myself, but as someone who comes with a lot of community,” Amaya says of Ordway, who is an assistant professor at the UCLA College. “I made a commitment to the students who I am a teacher for. Engaging community means sustaining relationships and continuing to uplift them in all of the work that you do. To me, that meant developing a research project that included my students and the relationships I developed as a result of my work at Anawakalmekak.”

Those forged relationships include Gabrielle Crowe and Minnie Ferguson, both of whom are pivotal in the reforestation efforts.

Crowe, granddaughter of Chief Ya’anna Vera Rocha, is the co-chair and secretary of environmental sciences for the Gabrielino-Shoshone Nation of Southern California. Ferguson is the co-founder and director of education at Anawakalmekak. She is also an advisor for the Gabrielino-Shoshone Nation of Southern California Council.

“This is really the vision that our directors and Gabrielle’s grandmother had for the school,” Amaya says. “Gabrielle and so many others are helping bring that vision to life.”

“This was a really important opportunity to connect, engage and build relationships that I think honor the commitment that UCLA is making in its Strategic Plan,” says Ordway, who is also co-director of the Congo Basin Institute at UCLA. In October, the university outlined a plan to broaden its commitment to inclusive excellence, starting with deepening UCLA’s engagement in local communities and around the globe.

“Ary came into the graduate program with strong expectations of what she wanted. Part of that was gaining more research experience, but a big part of it was doing research that would lift up Indigenous knowledge, Indigenous science and Indigenous voices — and doing work that’s really important to both her Indigenous community in Mexico and here in L.A.”