Homegrown fire prevention could save Amazon rainforest

Among the ashes in Brazil there exists hope, driven by efforts of small family farmers

As fires swept across the Amazon last fall, there was worldwide outrage. Everyone from youth activist Greta Thunberg to actor and makeup mogul Kylie Jenner swarmed social media. Instagrammers bombarded the United Nations’ page, demanding coordinated, international action.

As fires swept across the Amazon last fall, there was worldwide outrage. Everyone from youth activist Greta Thunberg to actor and makeup mogul swarmed social media. Instagrammers bombarded the United Nations’ page, demanding coordinated, international action.

The flames have since died down, and news publications shifted their focus to politics and, later, the catastrophic brush fires in Australia. But the primary reason the Amazon rainforest burned —deforestation — remains a concern as farmers continue burning land to make room for cattle ranching and agriculture.

It is a problem that could come with a tipping point, said William Boyd, a UCLA environmental law professor.

“Roughly 17% of the Amazon has already been deforested,” said Boyd. If that number gets up to 25%, he said, some scientists believe it could trigger an irreversible transformation from tropical forest to grassland. “It’s hard to get people to recognize the urgency of the problem here in the U.S. — it still seems like the problem is a long way away.”

Brazil’s government, led by far-right president Jair Bolsonaro, exacerbated the problem by last year revising the country’s forest code — historic legislation that protects the Amazon — to grant amnesty to those who engage in illegal deforestation. Bolsonaro’s rhetoric also hasn’t helped either. Amid global outrage, he downplayed the fires and bizarrely blamed actor and environmental activist Leonardo DiCaprio for helping set them.

Within this sobering reality, hope remains. Family farmers and people who own small plots of land are reducing deforestation caused by their own land use practices.

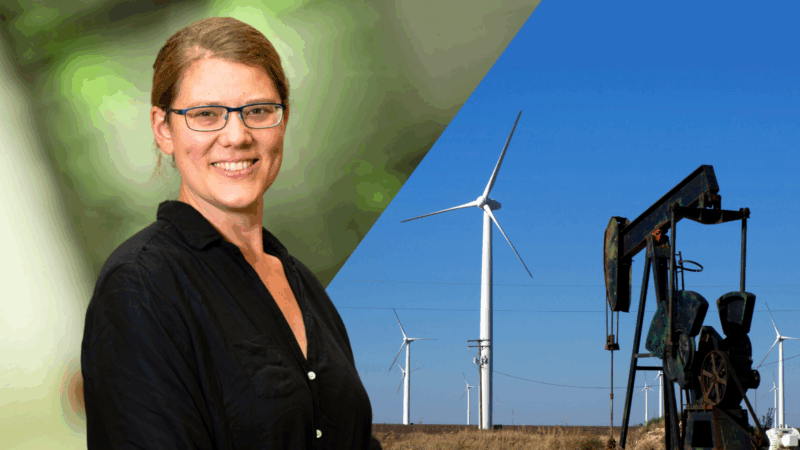

Erika Pinto is an ecologist with the Brazilian nonprofit IPAM, which works to help smallholders become sustainable. She said unsustainable agricultural practices employed by family farmers is “much more a reflection of lack of opportunity than a choice.”

Smallholders lack security and access to basic services such as healthcare or incentives to regulate their property from an environmental standpoint, Pinto said. IPAM provides training and techniques to manage forests and limit damage from fires. From 2012–2017, the organization helped 630 families increase gross income while reducing 80% of their farms’ deforestation.

Another glimmer of hope comes from the 2009 Moratorium on Soy, said Cesar Martinez Alvarez, a UCLA political science graduate student who studies agro-economics in Brazil as an example of citizen-driven activism that creates tangible change. Soy cultivation was responsible for massive deforestation prior to the moratorium, which compelled companies not to buy from traders who get their supply from farmers who clear rainforest. The moratorium arose from cooperation between NGOs and agricultural corporations who worked together to meet citizens’ demands. The agreement depended upon the idea that public disapproval can cause companies to improve their sustainable land use standards.

These actions are not comprehensive, but they’re part of the solution. Forest conservation is a critical part of fighting the global climate crisis, said Professor Boyd, who serves as the project lead for the Governors’ Climate and Forests Task Force, a coalition of 38 states and provinces from 10 countries working to stop tropical deforestation. He said citizens should pressure local and national governments to collaborate with Brazilian states that are stepping up to protect forests.

Boyd also emphasized the importance of private sector efforts to channel investment in ways that promote forest protection and to eliminate deforestation associated from major agricultural commodity supply chains.

The success of Brazilian family farmers shows how sustainable practices can protect the Amazon from the bottom up, and the Moratorium on Soy demonstrates how activists can compel governments and large companies to change their ways. That’s good news for social-media activists, who — even from a continent away — can use their voices to protect one of the planet’s most vital natural resources.

Main image: Rainforest Partnership