The $77 billion bug invasion

Ten species of invasive insect account for $77 billion in annual global economic damages, according to the first in-depth study on the subject, published today in Nature Communications. Even that…

A swarming, alien horde is here, and they’re hitting us where it hurts—our bank accounts.

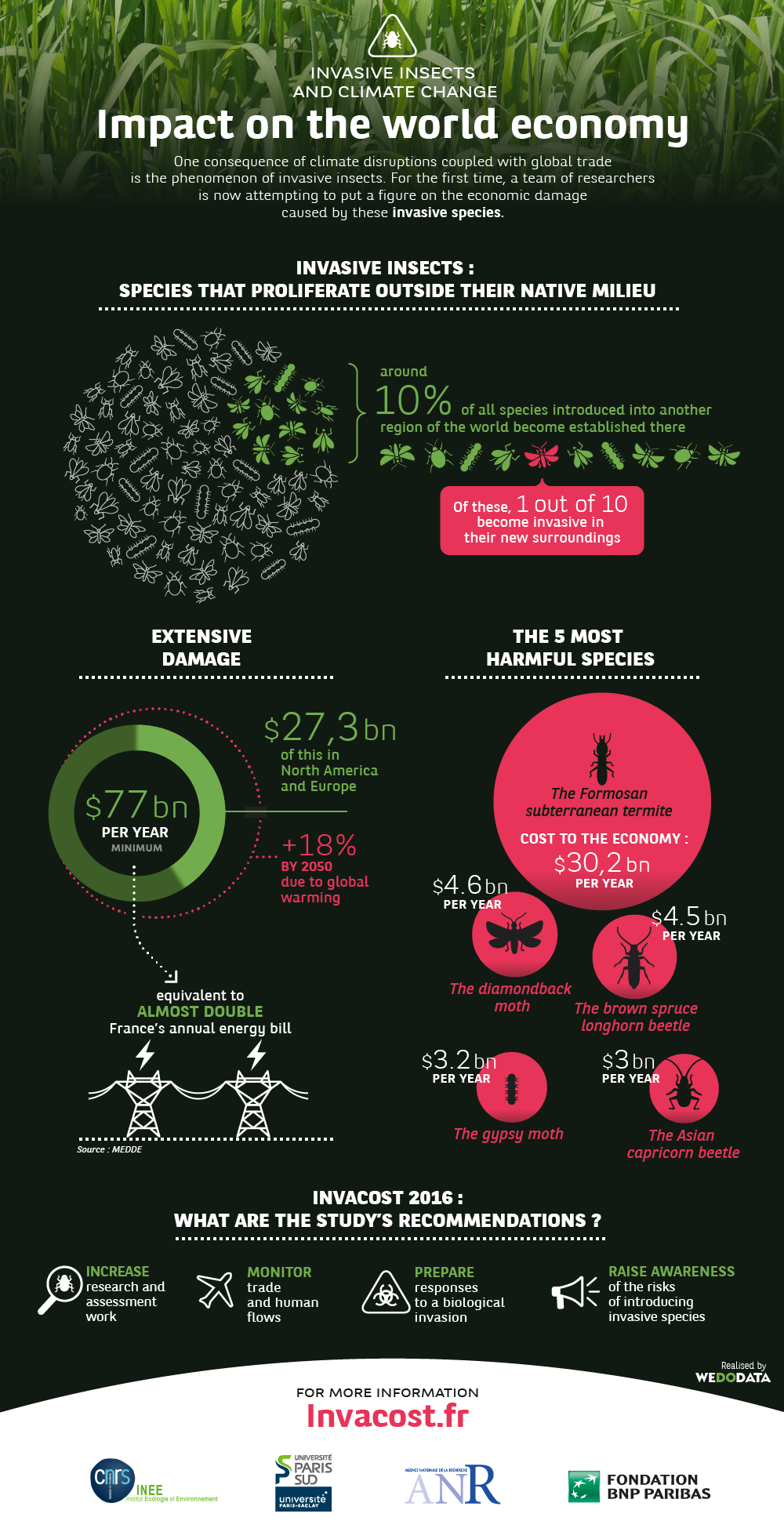

Ten species of invasive insect account for $77 billion in annual global economic damages, according to the first in-depth study on the subject, published today in Nature Communications.

Even that estimate is extremely conservative. Author Franck Courchamp, a French conservation biologist who researched the paper as a visiting professor at UCLA, said reliable studies on invasive bugs are limited in many parts of the world, and the paper’s researchers only looked at ten of the worst offenders.

Courchamp estimated that actual global cost of those ten is probably closer to $270 billion.

“The cost is enormous,” Courchamp said. “And there are thousands of species we have not studied.”

The paper analyzed the cost of pests such as Asian long-horned beetles, Formosan subterranean termites, red fire ants and tiger mosquitoes. They caused economic losses in a variety of ways: decimating crops and forests, destroying and devaluing real estate, and spreading diseases like malaria, yellow fever and Zika virus—which generate health care and prevention costs.

The Formosan termite was the worst perpetrator, accounting for over $30 billion annually by gobbling up buildings and infrastructure.

The project, which was funded by the BNP Paribas Climate Initiative Programme, looked at more than 700 existing studies on invasive insects. The researchers analyzed them for reliability, looking closely at sources, methodology and whether they were able to be successfully replicated.

Not all imported insects become invasive. Only about 10 percent are able to establish a successful population, and just 10 percent of those are deemed invasive—meaning they cause environmental, health or economic problems.

Climate change will make the problem significantly worse, Courchamp said. As global temperatures rise, invasive bugs will migrate further from the tropics and to higher elevations, as the cold winters that normally kill them become less harsh. The study estimates that 18 percent more territory will be available to invasive insects by 2050.

Preventing and controlling biological invasions is a difficult task.

“Invasions are mostly caused by global trade,” Courchamp said. “It’s difficult to tell people that we should put more biosecurity in place. It’s costly.”

One example is ballast water in ships, which is picked up from one port and deposited hundreds or even thousands of miles away, along with all the species that come with it.

In a statement at the Third Annual Ballast Water Management Summit in Long Beach, California, John Butler—president and CEO of the World Shipping Council—estimated that proposed new regulations requiring treatment systems would cost the industry $60 billion dollars. But he also noted the importance of dealing with the issue.

“The purpose of those regulatory systems is to prevent various forms of environmental harm,” Butler said. “That means that the mechanisms that we choose to protect those resources have to function from a scientific, technical and operational standpoint.”

According to its website, United States Customs and Border Security inspectors—equipped with x-ray machines and trained dogs—already intercept “tens of thousands” of invasive pests each year among the “millions of pounds of fresh fruits, vegetables, cut flowers, herbs and other items” that enter the country.

The threat of these pests is all too real for Raoul Adamchak, who manages the seven-acre, organic student farm at University of California, Davis. Organic farmers have an especially tough time, lacking pesticides and other tools of conventional agriculture. “Invasive pests usually come without any predators or parasites, which makes it really difficult to control them,” Adamchak said. Farmers can fight back by introducing new predators and parasites, but to do so, they must go through a lengthy approval process with the U.S. Department of Agriculture. It can take up to ten years.

In the short term, that’s bad news for Adamchak’s bok choy and Chinese cabbage, which were decimated by the invasive bagrada bug. The food would have been used to feed students in the university’s dining halls.

“Both of them were essentially a complete loss. It’s really disturbing,” Adamchak said.

UCLA ecologist Thomas B. Smith, whose research center hosted Franck Courchamp while he was working on the study, said climate change-driven spread of invasive bugs could affect many global communities’ basic survival.

“The folks who are going to be hit worst are the poor folks, the underdeveloped countries that don’t have the resources to deal with it,” Smith said. “For the Sudanese farmer who lives at 4,000 feet and isn’t experiencing these insect pests now, they’re suddenly going to be experiencing them. What are they going to do? They live day to day.”