The Ridiculously Resilient Ridge and California’s extreme weather future

Daniel Swain elevates weather talk to the stratosphere. He’s a Ph.D student studying atmospheric patterns and extreme weather at Stanford University. He’s also the creator of the California Weather Blog,…

There’s a reason people like to talk about the weather. Aside from being an easy way to get through casual social encounters, it’s something that affects our lives every day—and it’s changing on a global scale.

Daniel Swain elevates weather talk to the stratosphere. He’s a Ph.D student studying atmospheric patterns and extreme weather at Stanford University. He’s also the creator of the California Weather Blog, an expert source that people are increasingly turning to during these times of El Niño and severe drought.

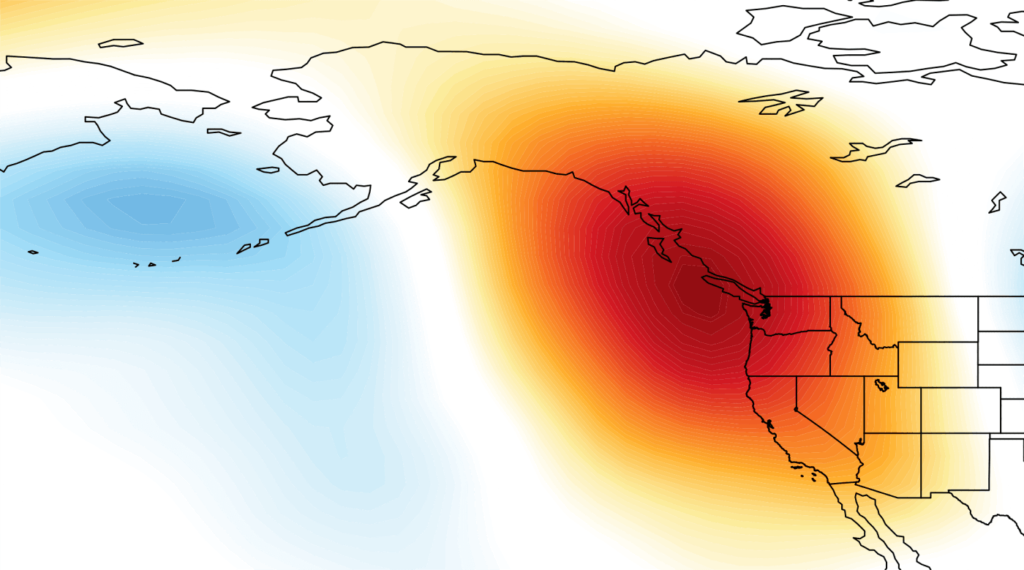

Swain and his fellow researchers spent the past several years investigating the Ridiculously Resilient Ridge—“Triple R,” for short—a persistent high pressure system over the Pacific Ocean. The Triple R deflects storms to the north of California, preventing the parched region from receiving its normal rainfall.

“It’s the main reason we’re in a drought,” Swain said. “It’s the persistence of this ridge during the winter months.”

Because of Triple R and other large-scale atmospheric conditions, the state will likely experience more extreme weather in the future. That’s according to Swain’s most recent research, which was published last Friday in Science Advances. Looking at the past 60 years, Swain and his team worked backwards from weather conditions—such as temperature and precipitation—to underlying atmospheric phenomena that cause them. They relied on data from satellites, planes, balloons and weather monitoring stations provided by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

“We looked at the atmospheric patterns associated with many of California’s extremes—not only dry years, but also wet years, warm years and cool years,” Swain said.

They found that drought-causing climate patterns have increased, but not at the expense of extreme wet weather-causing ones, which have become more frequent, too. This supports existing research that projects an increase in extreme weather associated with climate change, both in California and globally. “The fact that we’re seeing an increase in dry patterns but potentially also an increase in wet patterns at the same time is consistent with climate model expectations,” Swain said.

The bulk of previous climate research has focused on changes in average temperatures and precipitation. While that information is important, focusing solely on gradual outcomes tells an incomplete story.

“When we only look at the average, we might be missing a lot of what’s going on in the climate system,” Swain said. “It’s the extremes that matter from an adaptation standpoint.”

California is naturally a land of extremes, with a long history of drought and flooding. This study provides hard evidence that the atmospheric conditions associated with these events have become more common—something policy makers and the public should take into account when planning for the future, Swain says.

While the results focus on the western United States, the climate features the researchers studied exist around the world. In fact, the researchers designed the study specifically so their methods could be easily replicated to shed light on climate realities in other regions.

The human, everyday realities of weather are what inspired Swain’s research in the first place. Living in the Bay Area, he said it’s been “personally disconcerting” to be able to walk outside wearing a t-shirt in January.

Swain doesn’t plan to pull his head out of the clouds any time soon. Next, he plans to take his work to Southern California, where he will join climate researchers at UCLA. He hopes to take a hard look at atmospheric rivers—concentrated plumes of moisture that are thousands of miles long and hundreds of miles wide. The rivers provide a large percentage of California’s precipitation and are associated with almost all major flood events along the west coast.

Understanding how atmospheric conditions work is important to scientists like Swain because of their relevance to the millions of people living below.

“These are questions that have personal relevance for a lot of people,” Swain said. “To be able to give a concrete answer that we can stand behind from a scientific perspective is important.”