UCLA seniors model flood vulnerability in Tobago

Students traveled to Tobago to test their flood-risk model and gather local perspectives

Slash-and-burn farming and increased surface runoff from urbanization in Tobago have made the small Caribbean island prone to flooding from rivers and streams.

And, as the population of the 116-square-mile island has grown, more residents have settled in parts of the island with high flood risk.

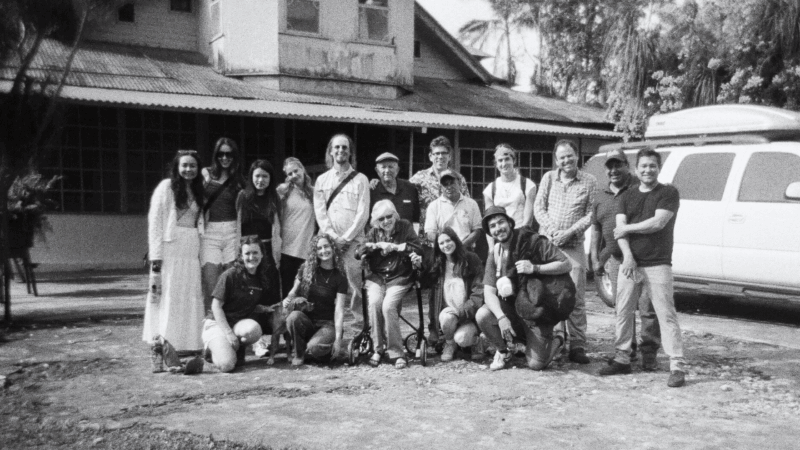

To identify the most vulnerable communities, seven UCLA students developed climate models as part of their capstone project for their environmental science bachelor’s degree. This spring they traveled to Tobago — the smallest of the two islands that make up the nation of Trinidad and Tobago — to collect on-the-ground data to test the accuracy of their maps and meet with collaborators at the University of West Indies (UWI).

The students assessed not just physical characteristics that influence where flooding occurs such as elevation, vegetation cover and soil type, but also socioeconomic factors that affect vulnerability, said Tyler Moy, the advisor of the project. Such factors included income levels, distance to emergency facilities and ability to access information about flooding from existing warning systems.

“The risk map can identify where interventions are needed, but to prove effective, the interventions have to be implemented while considering community needs,” he said.

Before the trip, the team used Geographic Information Systems (computer-based tools used to analyze geospatial data) and satellite images from Sentinel and Landsat (two major satellite programs) to create maps based on physical characteristics like land cover, slope and proximity to rivers in the districts of Roxborough and Castara.

While in Tobago, they collected on the ground-date like elevation and distance to drainage points, which they overlaid with digital elevation models and satellite images to refine their model’s accuracy.

With the help of the UWI students, they also spoke with community members to learn about difficulties they face due to flooding. Based on these conversations, they decided how much to weigh factors like access to flood relief and socioeconomic status in their vulnerability assessment models.

“They’re not just working with a dataset,” said Moy, a Ph.D. student in Environmental Health Sciences. “It’s a real place, real people are there and there are impacts.”

Conversations with community members revealed flooding contributors that the team didn’t even consider, said student Sydney Pearce, who led the satellite data analysis of the project. For instance, the Roxborough community has a high flood risk due to debris from discarded bamboo that clogs drainage.

When conducting work in a different county, it’s important to let locals“take the front seat,” said Pearce, who expects to graduate with an environmental science degree in June. The UWI students knew the local dialect, norms and how to best talk to the community members.

Additionally, the team identified nature-based solutions to flooding, such as landscape regeneration and agricultural techniques that reduce land degradation. They then created a flow chart that connects accurate risk assessments, early warning systems and community engagement — showing how these factors must be tied together for adaptation measures to succeed.

Population growth has outpaced infrastructural upgrades on Tobago, said Marie Inumerable, a student member who leads the Community Engagement portion of the project. Some residents in remote parts of Tobago have only one access road to the rest of the island, so flooding can leave them isolated and without an ability to receive help.

The models can help agencies such as Tobago Emergency Management better assess where flooding interventions are most needed by identifying high risk areas and areas where nature-based solutions may be most effective, she said.

During their free time on the island, both UCLA and UWI students snorkeled, explored beaches, sampled new cuisines and learned about the local culture.

“The UWI students were so hospitable to us,” Inumerable said. “They helped us understand what island life is like and the values of their education system: technical work and research but also a sense of community. This is something we hope to carry on here at UCLA.”

The project was conducted as part of the UCLA Institute of the Environment and Sustainability’s senior practicum, a year-long capstone program that pairs students with nonprofits, private companies and government agencies to solve real-world problems.

The team members are Karina Balekjian, Marie Inumerable, Pippin Jardine, Sky Lane, Mason Lehman, Sydney Pearce, Jorge Reque, and Sallyrose Savage (a graduate student assistant member of the project).

The team members (left to right): Mason Lehman, Karina Balekjian, Sydney Pearce, Marie Inumerable, Pippin Jardine, Jorge Reque, and Sky Lane.