Field notes from the finca: UCLA students trace biodiversity through Guatemalan cloud forest and coffee fields

Seven environmental science seniors funded their entire trip through a crowdfunding campaign, carrying their research from Westwood to the mountains of western Guatemala

At 5 a.m., the finca stirred to life.

A rooster crowed from somewhere behind the wet mill, and the faint scent of coffee curled through the chill mountain air. Seven UCLA students, still shaking sleep from their eyes, dressed in hiking clothes and sipped black coffee as mist drifted over the ridgelines. It would be the first of many mornings they would spend like this: booted, bundled and halfway up a mountain before sunrise.

They came to Finca Dos Marias — a century-old coffee farm perched 5,000 feet in the Guatemalan highlands — to study biodiversity across a working landscape. What they found was more layered: a living classroom where ecology, culture and community wove together in unexpected ways.

“When asked why I went to Guatemala for spring break, I guess the technical answer was research,” said Alexis Shenkiryk, the student communications lead of the project. “But truly not a single moment there ever felt like work.”

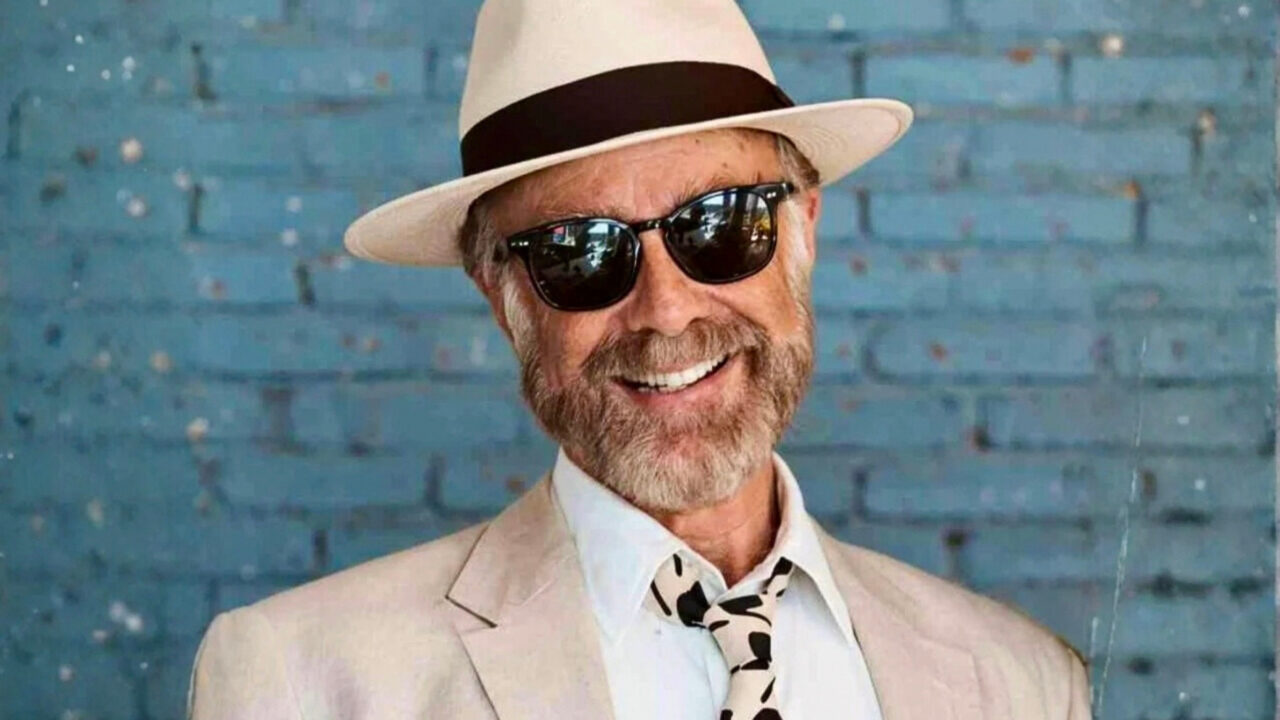

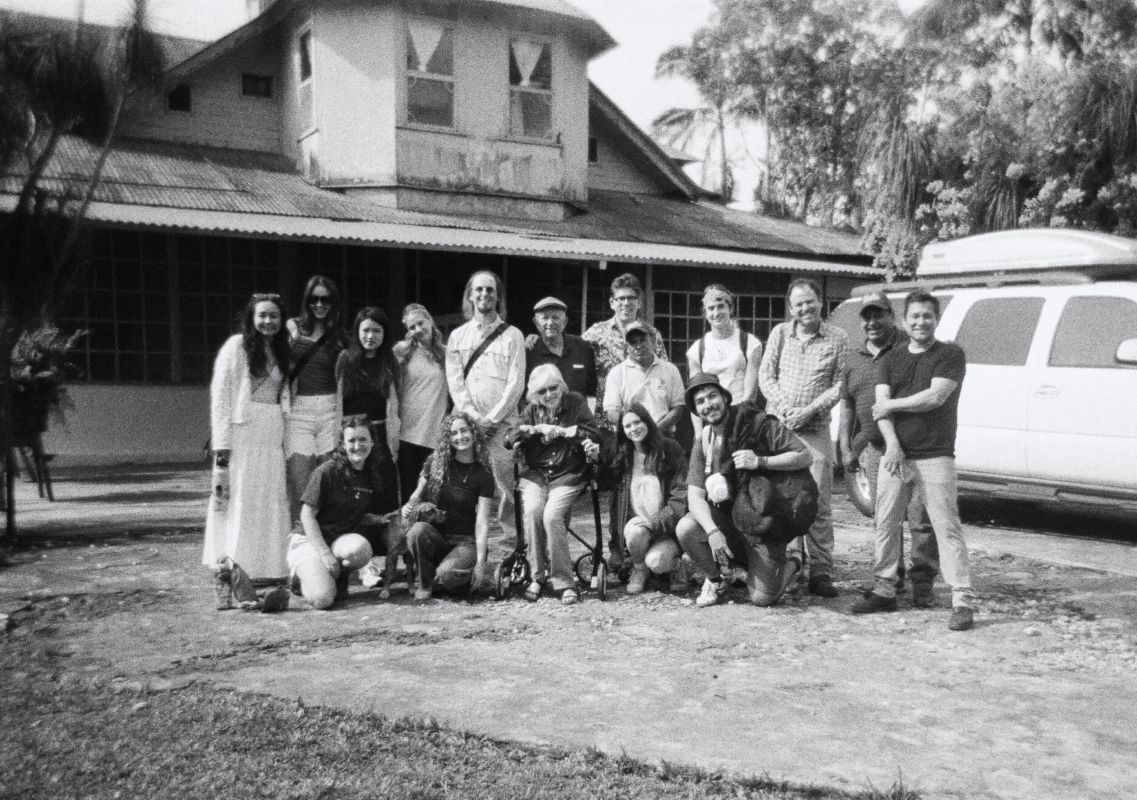

For a week in March, the group — seniors in UCLA’s Environmental Science program — rose before dawn, hiking into the cloud forest to collect data on native and often endemic species. Led by faculty advisors Dan Cooper and Ryan Harrigan, the students partnered with Jones Coffee Roasters, a Pasadena-based company that sources beans from the remote, family-owned farm in Guatemala.

They recorded sightings, cataloged songs and tracked how birds, insects and other species responded to the landscape, from shaded groves to clear-cut paths and cultivated slopes. Their aim was to map the intersection of biodiversity and farming — specifically, how different land use practices influence bird populations in a region where economic survival and environmental stewardship are deeply entwined.

The house they stayed in — a lemon-yellow relic with a weathered tin roof — was built from a Sears kit nearly a century ago, its walls hauled up the mountain on muleback. Inside, windows framed views of the valley below; books lined the sills, and a church down the path was strung with purple flowers for Holy Week. A place of memory, inhabited by five generations of the Asturias family and now managed in partnership with Jones Coffee, the finca radiated history.

Outside the house, the students spent their mornings collecting data on bird sightings and habitat conditions, learning to parse calls of emerald toucanets and other forest dwellers. The songs were unfamiliar but distinct; each a signal, a thread of data in their growing field notebooks.

“While we previously practiced our bird-spotting abilities in the Mathias Botanical Gardens at UCLA, nothing could have prepared us for the sights and sounds of the Guatemalan highland forest,” Shenkiryk said. “The early wake-up call was entirely worth it.”

In the afternoons, the team observed the agricultural side of the equation: touring the farm’s beneficio, or wet mill, where coffee cherries are washed, dried and sorted. They explored the full arc of coffee production — crossing fields lined with rows of seedlings, tracing the journey from bean to cup, understanding not only the process but its environmental contours: the way soil health, shade cover and runoff might influence both yield and the species that inhabit the land. What began in classrooms and Zoom calls came alive with every step on the farm.

What set the project apart wasn’t just the science, it was the context. For some students, it was their first time abroad. Their presence at the finca was the result of months of planning, partnership-building and a successful crowdfunding campaign that covered the entire cost of the trip. It was proof that global research experiences could be accessible, not exclusive.

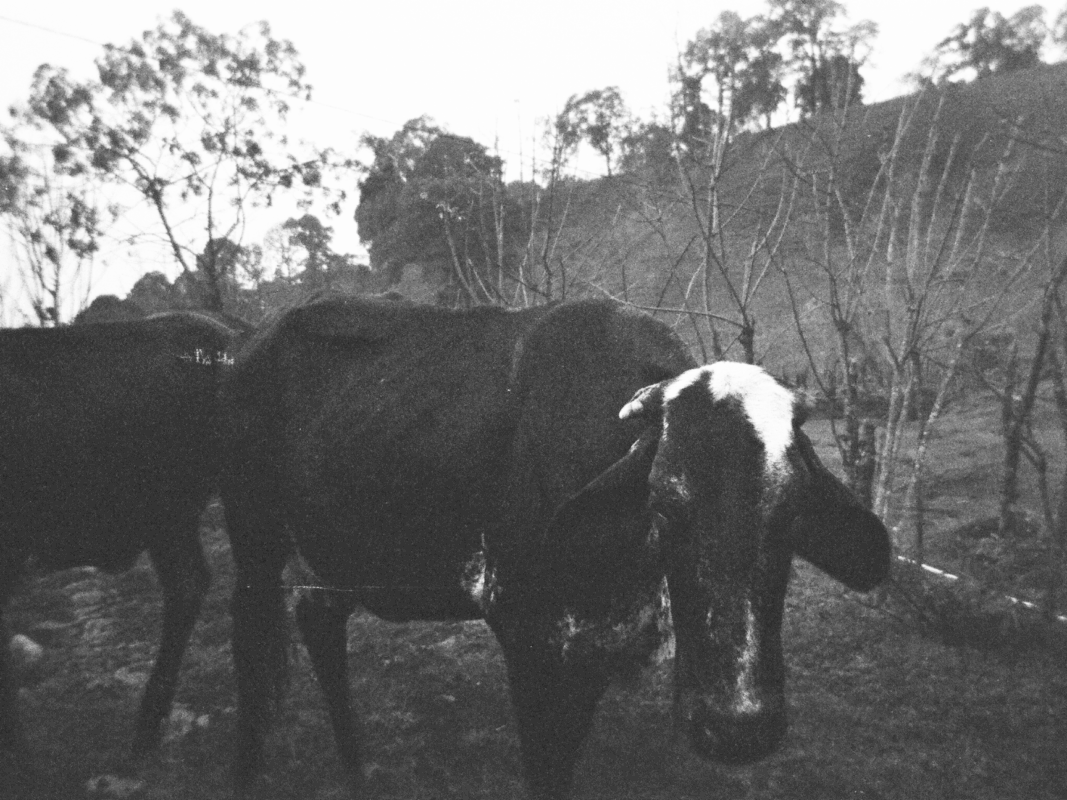

The days were rigorous; the hospitality, constant. Meals — prepared by Amalia, the finca’s head cook — were shared with the Jones family, farm workers and researchers. Conversations flowed in Spanish and English, over dishes of traditional Guatemalan tamales, queso fresco from the farm’s cows and bottomless baskets of warm tortillas.

“Our group dispersed among the Jones family and employees of the farm at the dining table that fit twenty of us,” Shenkiryk said. “Although each conversation held nuggets of information to extract, my favorites were the ones shared by Mireya Jones, the family matriarch, at the head of the table.”

Each night ended with pen to paper — birds identified, trails traced, questions raised. One evening, the group stumbled across a decades-old guest book. Flipping through the pages, they found a familiar name: their own advisor, Dan Cooper, who had visited the farm in 1997. “I hope to return someday,” he had written.

“On behalf of all my practicum members, I can say with certainty that we hope to as well,” Shenkiryk said.

Back in Los Angeles, the group is now analyzing their data — tracking bird activity across decades and across the highlands, from intact forest to cultivated coffee fields. As sensitive indicators of environmental change, birds offer a lens into ecosystem health. Compared to notes from Cooper’s visit in the late 1990s, the students found signs of renewal: more species, more movement and a forest that appears stronger than it was a generation ago. It’s a hopeful shift, suggesting that even altered landscapes can foster recovery under the right conditions.

“Looking back on the work, I went into it as an instructor and advisor. But once we hit Guatemala, that child-like sense of wonder re-emerged,” Harrigan said. “It was great to see three generations of ecological caretakers thinking about some of the issues we face, and I have no doubt this next generation of scientists will be right there with the solutions.”

As one of the final steps before graduation, the Guatemala practicum offered more than research experience. It revealed what environmental work could look like outside a lab or lecture hall. A slower, more connected way of doing science came into focus — one where fieldwork means early mornings and muddy boots, and where the lessons extend far beyond the page.

“It was an experience steeped in color and knowledge, and undoubtedly a key part of my undergraduate career,” Shenkiryk said. Like the finca itself, their work is a study in balance: between past and present, production and preservation. Between where the coffee grows and the birds sing.

Photography by Iris Hong, UCLA Environmental Science senior and Guatemala Practicum team member