Tech meets tradition for rainforest conservation project

If you happen to have a friend who lives on the other side of the planet, advances in satellite technology make it easy to stay connected. Satellite-based technology also makes…

NASA and UCLA use International Space Station to learn how animals disperse seeds in Congo Basin.

If you happen to have a friend who lives on the other side of the planet, advances in satellite technology make it easy to stay connected.

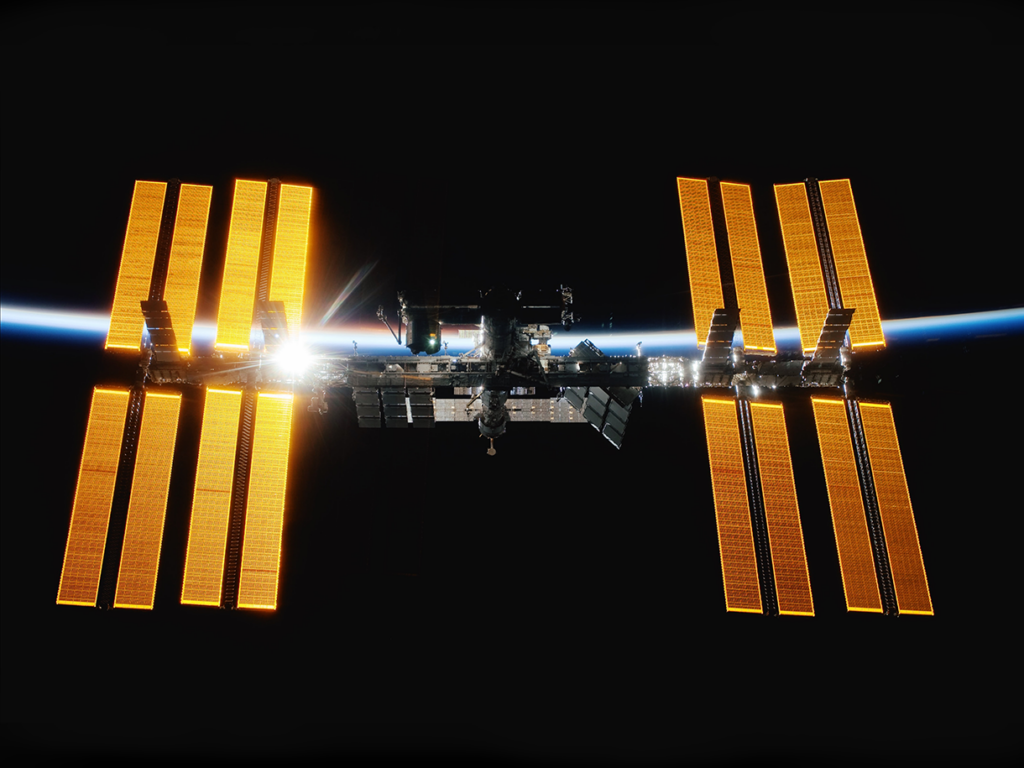

Satellite-based technology also makes it easy for conservation scientists to stay connected with animals around the world. While it’s not quite possible to Facetime a chimpanzee, they can pinpoint its location, learn how far it is off the ground, how warm the air around it is, and even what nearby trees look like. The International Space Station tracks birds, antelopes, monkeys and more — over 800 species in total, covering nearly all of Earth’s surface as it orbits the planet 16 times a day. Satellites have become an extraordinary tool in conservation science.

UCLA and NASA experts are now partnering to take advantage of this technology, combining on-the-ground research approaches with emerging technology and datasets to better understand how animals affect where trees grow. That knowledge could help conservation efforts.

“If you look at many tropical forests, 90% of the trees are dispersed by vertebrates,” said Tom Smith, co-author of the project proposal, which was greenlit earlier this year. “People forget the role these animals play in the regreening of the rainforest. If you lose your elephants, primates and birds, forests can’t regenerate.”

Smith, director of UCLA’s Center for Tropical Research, began studying rainforests over 35 years ago. Then, the most advanced way to track animals was through very high frequency radios, which had a range of 25 square kilometers and required two researchers to stand several kilometers from each other using hand-held antennas. The International Space Station effectively multiplies that range by over 10 million, and researchers don’t have to move an inch.

Satellites offer more than remote tracking. An instrument called GEDI, for example, sends lasers to the Earth’s surface to record its 3D structure. This helps scientists understand how structural patterns of the forest canopy correlate with movement of seed dispersers. Another instrument, ECOSTRESS, records temperatures to help scientists understand how warmer and cooler places affect where the animals travel.

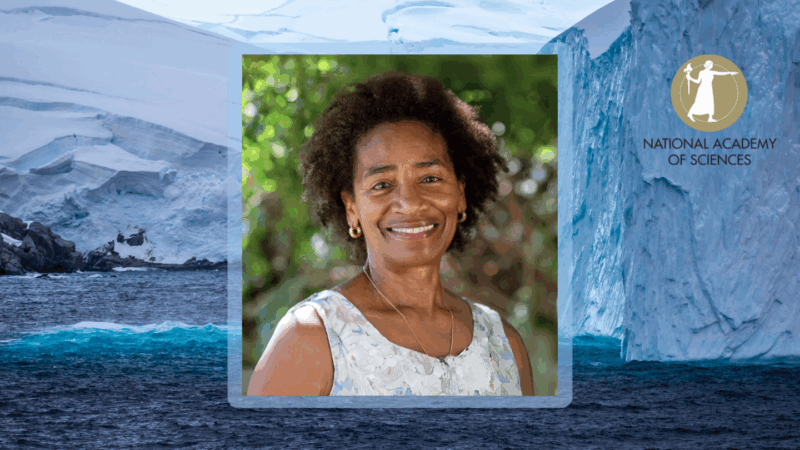

UCLA environmental scientist Elsa Ordway, co-leader of the project, said scientists advancing analysis-by-satellite are thinking at a rainforest-sized scale. They can identify overall structural patterns of height and the contours of the rainforest canopy — but rely on other ecology specialists to understand how those variations relate to animal behavior. For example, Smith once mentioned to Ordway that hornbills, birds native to the Congo and important seed dispersers, need very large trees to nest. “That clicks for me,” Ordway said. “That has major implications.” Forests selectively logged for big trees might otherwise seem like a sustainable way to harvest lumber and leave most of the ecosystem healthy and intact.

Tom Smith is familiar with the ‘a-ha’ feeling prompted by a chat with someone who thinks differently and offers a different kind of expertise. Throughout the years, he’s gained many insights through conversations with the Baka, a group indigenous to the region. Research suggests that the Central African community of hunter-gathers belong to one of the most ancient lineages of modern humans, with roots going back about 200,000 years. They’ve been paying attention to the forests they live in for an untold number of generations and share what they know with Smith.

“They’ll mention some ecological detail you never heard of, and you’ll go — ‘What? Can you explain that again?’” said Smith, who has over three decades of experience studying the area. “To them it’s just a matter of fact, but it will be something completely new to western science. And 99.9% of the time they’re right.”

For example, once Smith was on a trek through the forest with Augustin Sec, a Baka and long-time friend and colleague, who he refers to as a “professor of the forest.” The Baka professor pointed to a fruit to explain that it’s dispersed by snakes. There is no record in scientific literature of snakes eating and dispersing the seeds of fruits. But Tom says he’d put money on it being true.

This UCLA/NASA project won’t track snakes — but it will track other animals crucial to rainforest health, and it will use a motley team to do it. Other co-leaders of the project include expert remote sensing scientists, Sassan Saatchi and Antonio Ferraz, based at UCLA’s Institute of Environment and Sustainability. Both bring decades of research experience in Central Africa. The project will also test hypotheses about species’ ranges that draw from traditional Baka knowledge. By bringing together indigenous knowledge and space-age technology, the collaboration seeks to develop a valuable new perspective on rainforest conservation.