UCLA Environmental Science and Engineering doctoral program turns 50

Alumni played major roles in global sustainability efforts across six decades

In the early 1970s — the infancy of the modern environmental movement — leaders in academia and public policy began to focus on growing problems like air pollution, water pollution and species loss, while climate change had not yet emerged as a dominant issue.

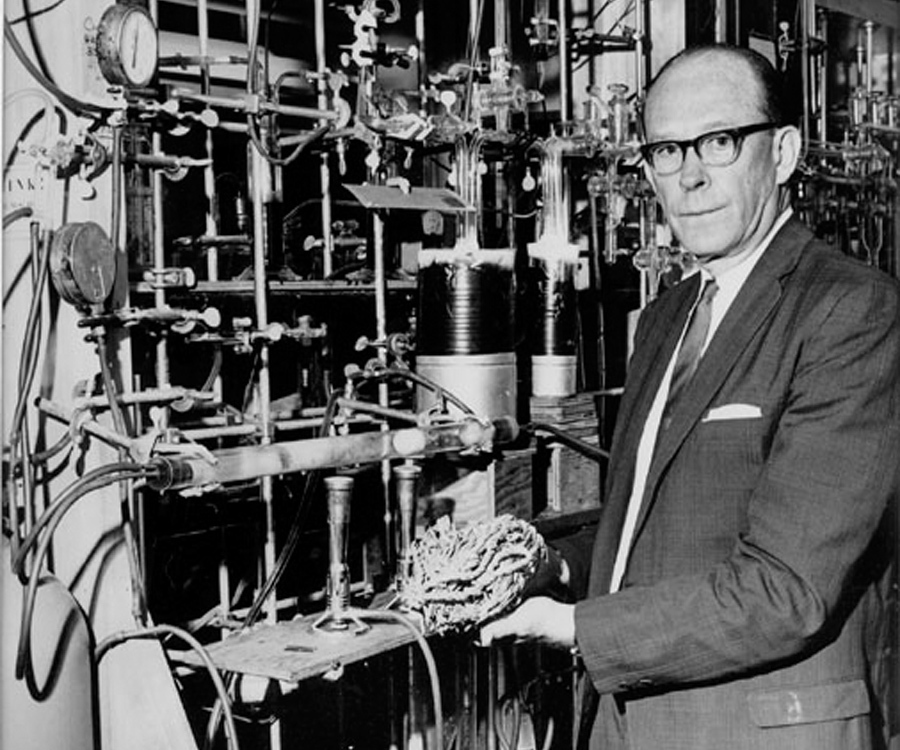

Nobel laureate and UCLA chemistry professor Willard F. Libby was one such leader. His work in academia and with government agencies such as the Atomic Energy Commission led him to conclude that experts were too specialized to handle the complexity of environmental problems, which involved dimensions beyond hard sciences, such as public policy, health and business management.

That belief led him to spearhead the creation of UCLA’s degree-granting academic program in environmental science and engineering in 1973. Fifty years later, the program is still going strong — and its graduates have played important roles across a broad range of sectors and specialties.

“It was one of the very first environmental programs,” said UCLA professor emeritus and former Environmental Science and Engineering program director Richard Ambrose. “The hallmarks of the program have always been its multidisciplinary approach to training students and a commitment to training professionals as opposed to academics.”

The Environmental Science and Engineering (ESE) doctoral degree combines intensive classes in a range of academic fields and practical experience through a residency program — after two years of coursework, students work on real-world problems through residencies with government agencies, businesses and nonprofit organizations as they work on their theses.

“When you talk to students years after they’ve graduated, they all say the broad scope of the program was helpful,” Ambrose said. “The hydrology class they never thought they were going to need was really useful, or they appreciated the perspective they got by taking environmental law.”

A global impact

Alumni of the program have made a worldwide impact, dealing with problems as diverse as environmental storytelling and making water supply sustainable as the world’s climate rapidly changes. They worked in high-level positions at businesses, agencies and organizations such as the United States Environmental Protection Agency, the Smithsonian Institution, Disney, Surfrider Foundation and the U.S. Geological Survey.

Setal Prabhu, who graduated in 2017, works as senior adviser in agency relations for Southern California Edison. She plays a critical role in connecting local, state and federal agencies as the state transitions from fossil fuels to renewable energy sources such as wind and solar.

“I wouldn’t even be here if it wasn’t for the ESE program,” Prabhu said. “I work with biologists, archaeologists, environmental engineers, electrical engineers, civil engineers, planners, lawyers, media. Having that that breadth of information ESE gave me helped me communicate across areas of expertise.”

Her time at UCLA also imbued her with optimism and an understanding of how important it is for people to change their behaviors.

“We’re being innovative, wanting to have renewable power or electrify our housing and transportation systems, and that’s all great,” Prabhu said. “What I don’t hear a lot of in this country is actual behavior change — peer behavior change that could contribute so much.”

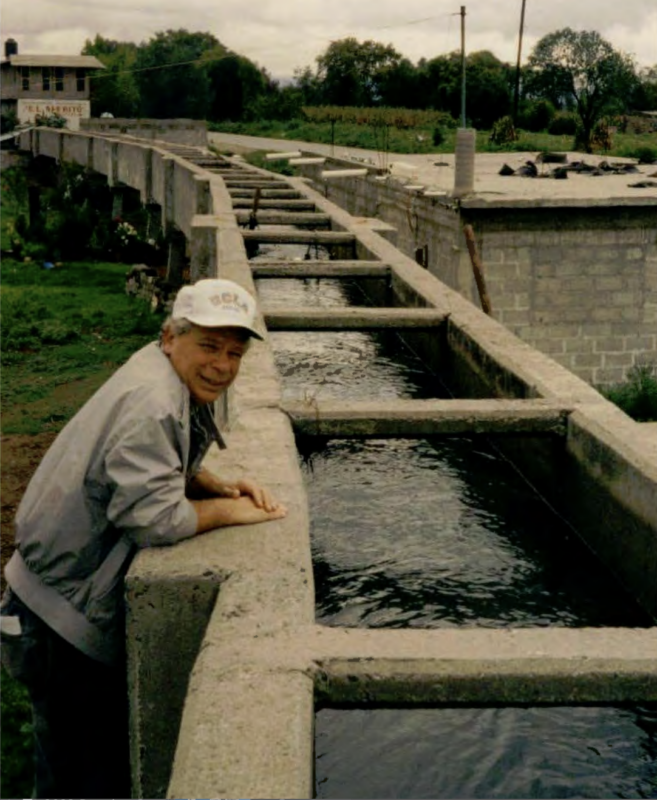

Wayne Stone, another ESE alumnus, was one of the program’s first students. After graduating in 1978, he embarked on a career making cities and towns more sustainable and resistant to climate change as an engineer, research scientist and consultant. Stone planned and designed roads and highways, water supply, waste management and other infrastructure and services in places like Manila, Ho Chi Minh City and Nepal, where he now lives.

“We suffer from climate injustice in Nepal, which emits less than 0.01% of global greenhouse emissions but experiences some of the worst impacts because of how fragile the environment is,” Stone said.

Because climate change is altering precipitation patterns, the Himalayan country faces worsening flooding, landslides and sinkholes, he said. His latest project, completed in June 2023, mapped these hazards and developed a climate-resilient road and drainage system in the city of Pokhara.

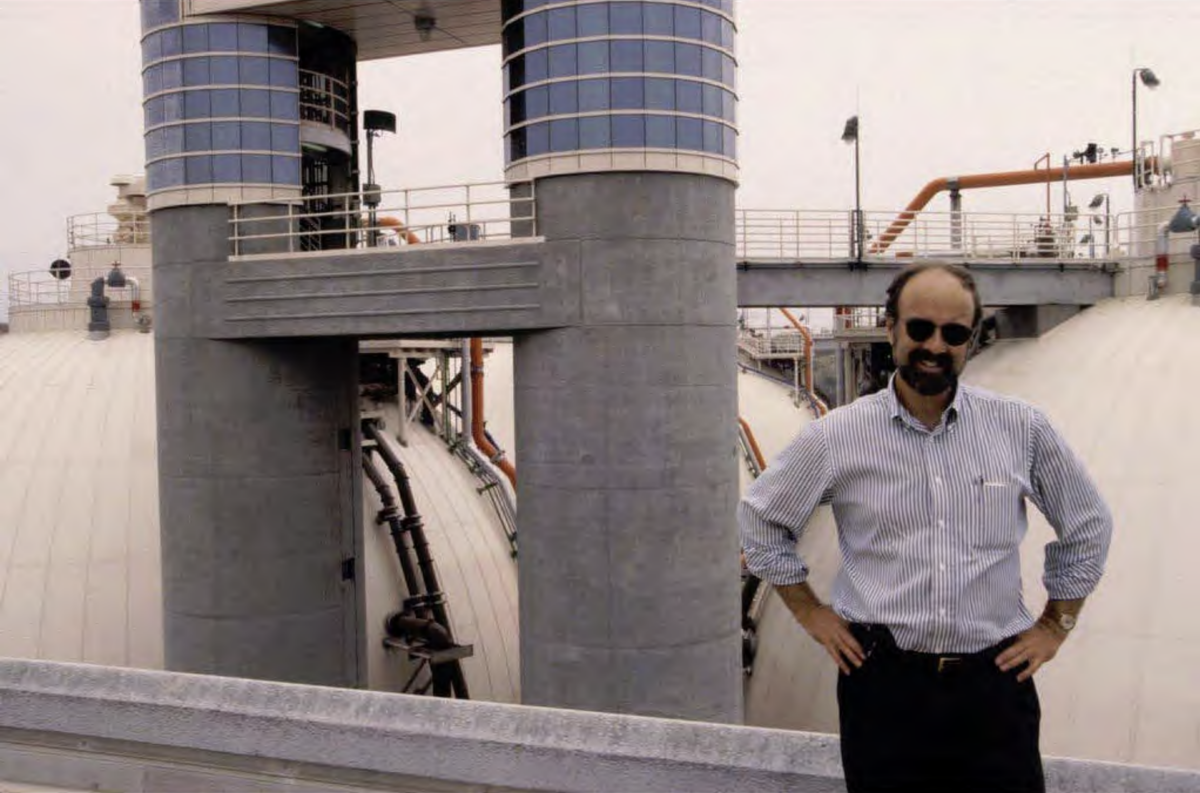

Robert Kawaratani also graduated in 1978. He took his skills to Japan, where he spent decades doing energy policy research and helping businesses perform life cycle analysis, a process that seeks to quantitatively understand the full environmental impact of products over their entire lifetime, from manufacture to repurpose or disposal.

While working for the international packaging company Nikon Tetra Pak K.K., Kawaratani helped develop Japan’s first type III ecolabel — a type created to high standards, providing consumers with research-generated information about products that has been verified by a third-party certification organization.

Kawaratani was at the fore of a global shift as new government policies and consumer preferences drove companies to get sustainable. He said his education in the ESE program, which included classes on economics and public policy as well as sciences, helped prepare him for the task.

Though he retired about 10 years ago, Kawaratani said transitioning to renewable energy isn’t a one-size-fits-all proposition.

“The energy transition is going to look different for various countries,” Kawaratani said. “If you’re the United States and have lots of sunny space,” the capacity for solar power is greater. “Japan is looking to hydrogen and using ammonia as the energy carrier for power generation.”

A little closer to campus, 2014 alumnus Dave Quiros leads a team of 35 at California Air Resources Board. They are responsible for complex technical analyses that underly regulations, incentives and other initiatives to clean the air and mitigate effects of climate change. Their work factors heavily into ambitious statewide efforts to phase out combustion engines in new cars by 2035 and meet federal guidelines for clean air.

The team also performs technical analyses behind policies like Advanced Clean Fleets, a program that aims to make California’s heavy-duty trucks and buses produce zero emissions by 2045.

Zero-emissions cars and trucks are only part of the puzzle, though. Other motorized vehicles contribute a significant proportion of overall emissions in California. Aircraft, locomotives, ocean-going vessels, even industry and housing — all are important factors that must be considered by policymakers, Quiros said.

“I help show, using numbers, that those sources are contributing a lot of the problem so our air quality models can be informed and they can make the right policy decisions,” he said.

Those decisions also must take economics into consideration. “We generally aim to make it so that the cost of the regulation is cheaper than the benefits that are going to be provided in return,” Quiros said.

Like other alumni, Quiros said the ESE program’s educational breadth helped him see the big picture, with policy and business classes helping him understand important context for his team’s technical work. Meanwhile, the practice-based aspects of the program allowed him to hit the ground running and accelerated his career progression, he said.

The UCLA Doctor of Environmental Science and Engineering (D.Env.) program offers a rigorous and interdisciplinary curriculum that provides advanced coursework with cutting edge research.

Expert problem-solvers for the next 50 years

Though the ESE degree program has evolved over time, its core values remain as important as ever, said Travis Longcore, faculty co-director of the program.

“This is about applying knowledge and being able to work in the non-academic setting of agencies, consulting and implementation of environmental protection and restoration,” Longcore said. “As humans, we keep getting ourselves into these ruts, and it takes people with serious know-how to get us out again.”

A lot has changed since the 1970s. Climate change is now advancing rapidly, and there is more need than ever for practicing experts who can deal with its effects. The world was about three degrees warmer (1.55 degrees Celsius) in 2022 than it was in the 20th century, and climate models forecast an even greater increase over the rest of the century without immediate and drastic reductions in carbon emissions. The effects of these changes are expected to affect the daily lives of people all around the world.

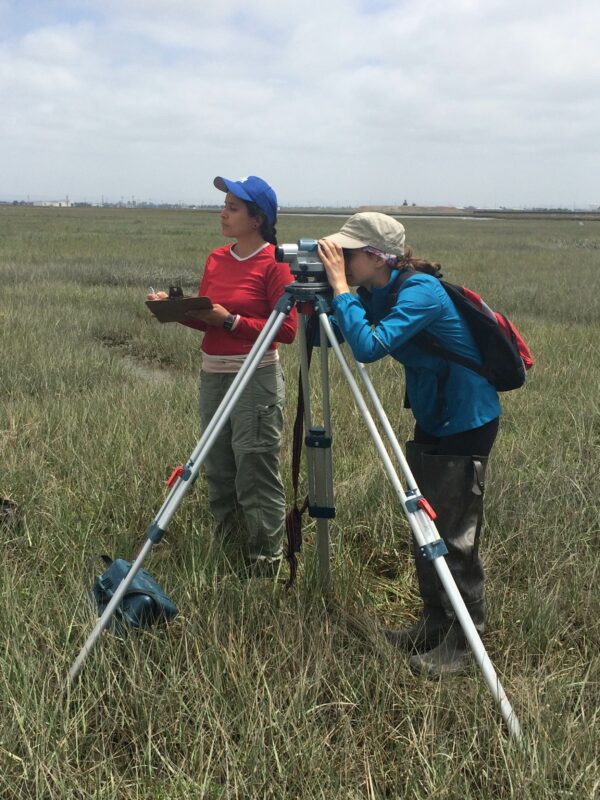

Getting people to work toward change, mitigate climate change and adapt to a changed world means ensuring access to nature. Current student Jenny Aleman-Zometa helps ensure all communities get a chance to enjoy nature, especially in urban areas, where 50% of the world’s population lives — a percentage that is steadily growing.

That means creating accessible green spaces. Aleman-Zometa works as a regulator for the Army Corps of Engineers while completing her dissertation. She served as program director for Los Angeles River State Park Partners, a nonprofit organization dedicated to supporting three state parks along the L.A. River, all of which factor into massive efforts to revitalize the concretized urban river, making it a more natural place for people and wildlife while continuing to protect the city from catastrophic floods that drove leaders to line the 51-mile river with concrete over 80 years ago.

As she completes her dissertation, Aleman-Zometa also works as a regulator for the Army Corps of Engineers, a federal agency leading complex efforts to restore the river with major projects that run into billions of dollars.

The work requires skill and knowledge in engineering, public policy and community engagement — things she learned through the ESE program.

“If you’re going to work for a government or something hands-on, you need to understand the law and the engineering side,” Aleman-Zometa said. “You need to know a little bit about a lot of things. I think the program is great for that.”

Other current students are also hard at work on complex problems: developing ways to get lithium for electric vehicle batteries with minimal environmental harm, working with NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory to understand environmental impacts with satellite data, improving water and waste management as the climate changes, and more.

—

If you’re interested in supporting or partnering with UCLA’s Environmental Science and Engineering program, please contact Rachel Scott Foster at rscottfoster@support.ucla.edu.