Zooming in on how climate change affects severe weather

UCLA weather expert Daniel Swain is part of a team that created a new four-step “framework” to more accurately test how climate change is pushing unprecedented weather events. It’s the latest study in a burgeoning field of climate science known as “extreme event attribution.” Testing their new framework, researchers found that human induced warming has increased the odds of severely hot weather across more than 80 percent of the globe.

Floods, droughts, heatwaves and other incidents of nasty weather are on the rise.

Each time one of these incidents happens, journalists want to know if climate change is to blame—and some scientists have been quick to say “yes.” That’s what happened in August when seven trillion gallons of rain flooded Louisiana, killing 13. Within two weeks, scientists from NOAA (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration) declared that human-induced warming made the extreme weather event 40 percent more likely.

The problem with such quick assessments is that they aren’t always precise. And while total certainty may be out of the question, a team of climate scientists from UCLA and other universities is aiming to make rapid attribution science as accurate as can be. To do so, they released a new framework in a study published today in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Lead by Noah Diffenbaugh, an earth system scientist with Stanford University, the team spent several years honing a four-step framework to test when global warming contributes to record-setting weather events, and to what extent. The framework accomplishes this by combining and comparing statistical analyses of climate observations with increasingly powerful computer models.

The researchers assessed which aspects of existing climate models do the best job of simulating individual weather upheavals, so only the most precise and consistent data is incorporated into their methodology.

Just as importantly—scientists the world over have access to this information.

“We choose publicly available data sets through NOAA along with other federal and international agencies. We didn’t run our own climate model simulations. We don’t have our own interpretations of satellite data. This is the data that’s already out there and people are using,” said co-author Daniel Swain of UCLA’s Institute of the Environment and Sustainability.

One of the team’s goals was to test their framework by examining record breaking events in multiple global regions, and to go beyond simply assessing extreme temperature and precipitation, which is the emphasis of most rapid attribution studies.

They evaluated four variables: Hottest month, hottest day, driest year and wettest five-day period.

Their findings paint a grim climate reality.

So far, global warming from greenhouse gas emissions has increased the severity and probability of the hottest monthly and daily events at more than 80 percent of the observed areas. “Our results suggest that the world isn’t quite at the point where every record hot event has a detectable human fingerprint, but we are getting close,” Diffenbaugh said.

Human activities have increased the likelihood of dry years and wet weather events by 57 and 41 percent respectively.

“We see an increase in the odds of extreme dry events in the tropics. This is also where we see the biggest increase in the odds of protracted hot events—a combination that poses real risks for vulnerable communities and ecosystems,” warns Diffenbaugh.

But while the researchers were able to account for severe weather in many locations, large parts of the world remain unknowns. Satellite data exists for the African and South American continents, but ground level observations are limited by a lack of weather stations.

Those data gaps worry Swain. “It shows that even now what we know about the world is limited by the fact we aren’t always looking. If we aren’t looking we aren’t seeing everything that’s changing.”

His concerns loom larger with the Trump administration moving to defund NASA’s earth monitoring programs—directly threatening vital satellite data. In defiance of Trump’s attempts to muzzle them, some NASA scientists have gone “rogue,” taking to Twitter to keep spreading the latest science and climate news.

Losing community data sets, which are currently stored on National Center of Atmospheric Research servers in Colorado, won’t just affect American scientists. Scientists around the world rely on the information, and there is serious concern about the continuity of experiments already in progress.

It’s a risk Swain doesn’t think we can afford because with climate change, “things are moving very quickly right now, faster than we are able to keep track of.”

For example, temperatures in the Arctic climbed above freezing this past winter, stunning scientists.

When the researchers applied their framework to the Arctic’s record-low sea ice in September 2012, they found overwhelming statistical evidence global warming had contributed to the severity and likelihood of the ice loss. “The trend in the Arctic has been really steep, and our results show that it would have been extremely unlikely to achieve without global warming,” said Diffenbaugh.

Such unprecedented weather extremes have pushed the climate conversation beyond simply mitigating carbon emissions, compelling world leaders to focus on how to adapt to this new reality. A growing community of environmental scientists think even those measures will not be enough, and that large-scale geoengineering interventions will be necessary.

Having accurate answers about what kind of ugly weather is likely and how frequently it could hit will aid decision makers in implementing strategies such as disaster risk management, infrastructure design, resource management and coastal retreat.

But human activity is still the greatest wild card in the climate gamble.

“One of the most amazing things to me is that the largest uncertainty in future climate is not uncertainty in our models, it’s actually what we do—how much carbon we emit over the next few decades that overwhelms all the other uncertainties” said Swain.

When it comes to cutting emissions, Swain said he thinks the window for making the large changes needed is quickly closing.

Top image: 2008 flooding in Sri Lanka. | Photo by Randveig (Wikimedia Commons).

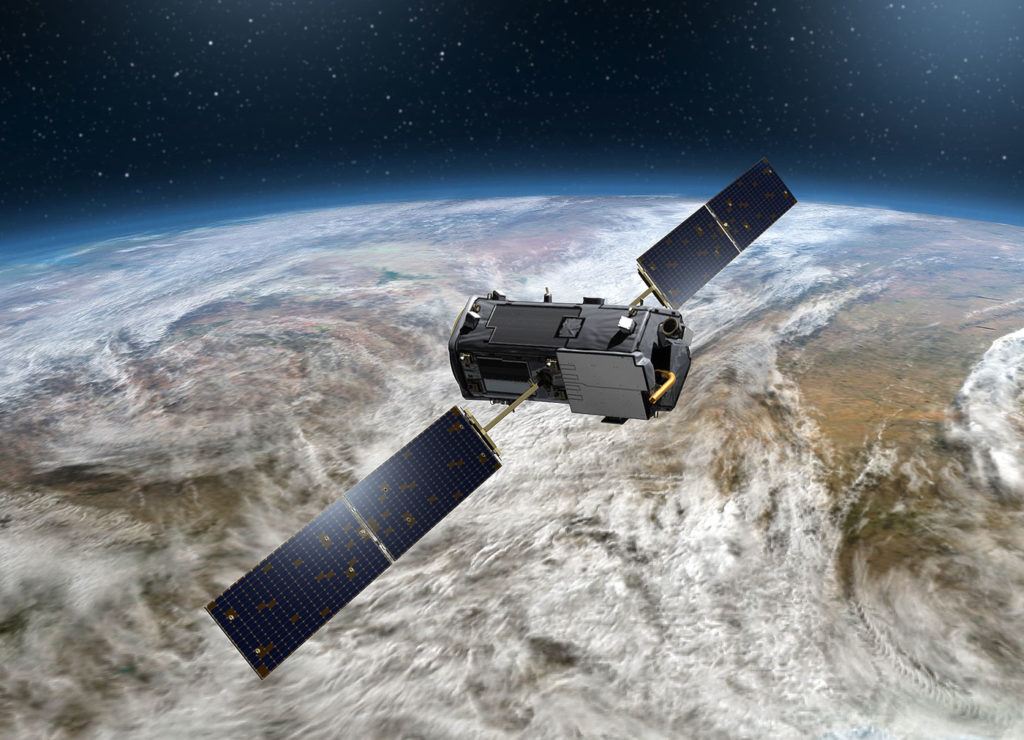

Second image: Orbiting Carbon Observatory 2, launched in 2014 by NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory. | Image courtesy of NASA.