State of Fire

UCLA wildfire research reveals the patterns and future threats of blazes in California — and offers a foundation for how to face the flames.

UCLA professor Brad Shaffer tracked the path of the Woolsey fire in November 2018 with dread.

Fire maps showed the biggest recorded blaze in the Santa Monica Mountains National Recreation Area was surrounding the field station where Shaffer’s center carries out conservation research. The fire was both savage and fickle. It reduced one building to rubble; less than 20 feet away, a second survived unscathed.

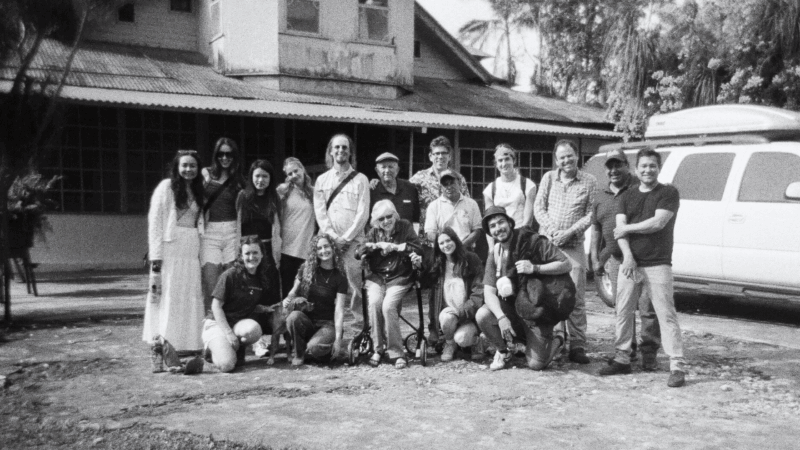

Two months later, dozens of students trekked through powdery black ash, as Shaffer led them across a different hillside, blackened by the fire, about 25 miles northwest of UCLA. Shaffer, an ecologist with expertise in wildfires, had partnered with researchers from the National Park Service and the U.S. Geological Survey to recruit nearly 100 students for a six-month study of the ecosystem’s recovery from the Woolsey fire, which burned through more than 150 square miles.

“It was horrible knowing the fire was headed for the field station,” Shaffer said at the time. “But staying discouraged doesn’t get you anywhere. So you move forward.”

That’s an attitude that keeps many UCLA researchers committed to the science of wildfires and climate change. In this case, it also meant a remarkable opportunity for undergraduates to conduct hands-on research. The researchers trained the student scientists, including 64 from UCLA, to take monthly observations of 340 one-meter-square study plots to determine how differing levels of fire severity affected plant recovery. The study would examine how small oases of less-severely burned areas influenced the return of plant and animal life. Dramatic variations of fire intensity have long intrigued Shaffer as a biologist, but as director of the UCLA La Kretz Center for California Conservation Science and its half-burnt field station, the issue had now become cruelly personal.

Almost two years later, Shaffer’s team is busily compiling the Woolsey fire data, but the picture is mixed. On one hand, there are signs of recovery, as ashen terrain has yielded to patches of brown dirt and weedy plant growth. At the same time, wildfires return with punishing force, sometimes outpacing recovery, notes Shaffer, a member of the UCLA Institute of the Environment and Sustainability.

“Huge amounts of land are burning up, and that’s particularly striking to me as someone who studies population fragmentation,” Shaffer says. “Humans have fragmented the wild landscape in so many ways, and the more isolated a plant or animal population gets, the easier it is for a catastrophic wildfire to take out that entire population. Fires have so many bigger impacts than just their acreage.”

The extreme year 2020

This year’s fire season has been devastating — the worst California has ever seen — and the statistics are staggering.

Through late October, which has historically been considered the end of California’s fire season, 8,834 fires burned nearly 6,500 square miles — more than three times as much land as the entire state of Delaware. It’s a dramatic increase from 2019, when 212 square miles burned.

Driven by climate change and exacerbated by poor management and fire response decisions, California fires are on the rise. The six most acreage-destructive fires in California history have occurred in just the past two years, and nine of the 10 worst have occurred since 2012. Ventura County’s Thomas fire in December 2017 was, at the time, dubbed the largest in California history. But in 2020, five fires — the August, SCU Lightning, Creek, LNU Lightning and North complex fires — outpaced it in the number of acres burned.

It’s not surprising that 2020 has been a record fire year. Los Angeles reached soaring temperatures in September, and L.A. County recorded its highest temperature ever when Woodland Hills reached a daytime high of 121 degrees Fahrenheit. On Aug. 16, Death Valley’s Furnace Creek reported a temperature of 130 F, the highest ever recorded on Earth since 1913, according to the World Meteorological Organization.

Blazing temperatures and erratic rainfall — both byproducts of climate change — provide the foundation for wildfires.

As a result, the fire season is longer than it used to be. Traditionally, fires peak in the summer and fall, but now the season has been starting as early as spring and lasting into the winter. The Thomas fire started Dec. 4, 2017, and was still breaking records of land and structural damage on Dec. 23. Fires in Oregon, Washington and the Sierra Nevada have also been larger and more frequent in recent years.

Adding to all the record heat is scant rainfall — even in places known for being quite damp. The U.S. Geological Survey says a combination of heat, drought and wind has led to this extreme, extraordinary 2020 fire season.

The conditions that give rise to wildfires are being exacerbated by climate change, and those conditions will continue to deteriorate in the future.

“I’m struck by the ubiquity of the fires,” Shaffer says. “I don’t think of Mendocino and Humboldt counties in the Pacific Northwest — with all their rain — or even the Bay Area as big fire zones, and yet the impact of air quality from fires was worse there than here [in Los Angeles]. People I know who moved to Mendocino County, in part to get away from wildfires, had to evacuate their homes. We think of fires as being somewhat confined to certain kinds of ecosystems, but it’s no longer the case.”

Some suggest that poor forest management is the sole culprit. That’s too simplistic, argues Stephanie Pincetl Ph.D. ’85, founding director of the California Center for Sustainable Communities at UCLA. As a professor-in-residence at UCLA’s IoES, she studies how to make cities more sustainable. Climate change is drying out plants and creating more fuel, and further thinning of small trees and controlled burning of underbrush is needed, she says. However, logging — which depends on killing environmentally useful larger trees — misses the mark, she adds.

Los Angeles Times’ interactive fire map has been tracking California’s 9,279 fires.

“If you’re just logging indiscriminately, you’re not really thinking about forest health,” she says. “You want to manage that forest to mitigate the dangers of forest fires, which means you’re thinning, you’re doing controlled burning, and you’re encouraging the growth of trees that will be big and healthy over the longer run. … You want trees that grow to 100, 150, 200, 250 years for their full ability to sequester carbon.”

As the new year approaches, dry and gusty conditions could result in elevated concerns in parts of Southern California, which may see more fires. The Santa Ana winds and Santa Barbara’s sundowner winds — blamed for the Thomas fire — howled well beyond early fall, blowing through Halloween this year. The Silverado fire near Irvine, which caused mandatory evacuations in an area that has rarely burned, started the last week of October and burned ferociously into early November.

Wildfires are here to stay

The conditions that give rise to wildfires are being exacerbated by climate change, and those conditions will continue to deteriorate in the future — a prospect that has drawn the attention of researchers and policymakers. For UCLA researchers, the race continues to provide information to government agencies, policymakers and the public that can help limit the devastation.

UCLA climate scientists Alex Hall, Daniel Swain and J. David Neelin have used climate models to project how California rainfall patterns will change, showing heavier storms during wet years and even less precipitation during dry years. The warmer the atmosphere becomes, the more water vapor it can hold at once, keeping water vapor aloft for long stretches of drought before a torrential release. The trio explained that this increasing “precipitation whiplash” could cause more winter floods and larger surges in plant growth, which is destined to crisp when deeper droughts occur.

This would create the same tinderbox conditions that have contributed to recent wildfires, says Swain, who hopes the trio’s 2018 research will be used by California’s disaster preparedness experts to plan ahead. In June 2020, Swain and colleagues released new climate-model research that shows climate change has already doubled extreme fire–weather days. Future increases will be even greater, but Swain noted that those could be mitigated by a reduction in greenhouse gas emissions. When California was filled with hundreds of wildfires, lightning strikes and fire tornadoes in August, Swain’s Twitter feed — popular with climate scientists and journalists alike — featured the pinned tweet, “This *gesturing wildly and in every direction* is utterly exhausting.”

Climate change is a global phenomenon, but Southern California is especially susceptible to its effects. It’s more prone to severe droughts than the northern part of the state, according to IoES’ Glen MacDonald, a distinguished professor of geography and an international authority on drought.

“We’re going to have our seasonally dry summer and that fine fuel is going to dry out,” MacDonald said when his team’s drought research was released in 2019. “If it’s a hot summer, conditions are ripe for wildfire.”

As far back as 2015, Hall led research projecting that Southern California’s wildfires would burn 64% to 77% more land by the mid-21st century.

It all paints a bleak picture of ever-worsening wildfires, which is one of the reasons why livable cities are a focus of the UCLA Sustainable LA Grand Challenge, a universitywide initiative that utilizes UCLA’s expertise and research to transform Los Angeles into the most sustainable megacity by 2050.

“Humans have fragmented the wild landscape in so many ways, and the more isolated a plant or animal population gets, the easier it is for a catastrophic wildfire to take out that entire population.” — Brad Shaffer, UCLA professor of ecology and evolutionary biology

Pushing for policy changes

Part of slowing the pace of wildfires is slowing the speed of climate change, which includes reducing greenhouse gas emissions by reducing energy use and minimizing the effects of droughts through better water management. Under the Sustainable LA Grand Challenge, UCLA research informed Los Angeles’ sustainability policies on energy conservation and water management, and 16 Sustainable LA researchers contributed to L.A. County’s first comprehensive sustainability plan. Thanks in part to the scope of the research and planning taking place on campus, UCLA Chancellor Gene Block co-chairs the city’s Sustainability Leadership Council with L.A. Mayor Eric Garcetti.

A comprehensive L.A. County biodiversity map, released shortly after the pandemic began, assists the public and policymakers by uniting disparate sources of county information into a publicly accessible map. Project leader Thomas Gillespie Ph.D. ’98, a UCLA geography professor, included a wildfire layer, which lets users check if a specific address is in a wildfire hazard zone. They can also view the often-overlapping outlines of every county wildfire since 1876.

None of the needed changes can happen without representation, notes climate researcher Aradhna Tripati. Tripati founded the Center for Diverse Leadership in Science at UCLA to elevate scientists who have been underrepresented. With a focus on justice and equity, the center has already supported more than 150 early career fellows in the last three years, including many dedicated to environmental science.

The six most acreage-destructive fires in California history have occurred in just the past two years, and nine of the 10 worst have occurred since 2012.

The ethics of fire service

One disturbing trend involves wealthier neighborhoods paying for private fire protection. That has created a socioeconomic gap between those who can pay to defend against fires and those who can’t, says Pincetl. She studies ways to make cities more sustainable, including a variety of issues related to wildfires, from forest management to the role of electrical utilities.

Pincetl notes that aging electrical infrastructure and its role in sparking wildfires is a legacy of the centralized power plant model. Decentralized forms of energy, such as rooftop solar panels, are needed to prevent both accidental blazes and the mass power outages intended to prevent them. She also advises policymakers to change zoning laws to limit construction in wild — and flammable — areas. Although climate change, drier vegetation and aging electrical infrastructure contribute to the increase in wildfires, the worst contributors by far are people, she says.

“Preventing wildfires at the urban fringe is going to require pretty substantial land use planning changes,” Pincetl says. “We can no longer build in fire-prone areas. That’s actually the only way you’re going to prevent igniting wildfires. … The more humans interact with this zone that is flammable and always has been flammable, the higher the chances of igniting a fire.”

The silver lining around the clouds of smoke from this year’s fires may be that people are finally paying attention, Shaffer says.

“It gives me hope that as fires become such a big part of the national conversation, the research has refocused on the reasons for those fires, and climate change is a real driver,” he says. “People are losing that standard Pollyanna view that we’ll learn to live with it, and that’s a positive step.”